The first hour of “EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert” is a compelling argument that Elvis Presley remains the greatest entertainer who ever lived. By the end, director Baz Luhrmann seems to be suggesting something approaching deification. The film, released on , isn’t simply a concert film; it’s a meticulously constructed shrine to the King, and a testament to his enduring power.

Luhrmann returns to the world of Elvis just four years after his 2022 biopic, “Elvis,” starring Austin Butler. While that film attempted a more traditional biographical narrative, it struggled to contain the complexities of Presley’s life, and legacy. “EPiC,” however, wisely focuses on what can’t be debated: the sheer, undeniable charisma of Elvis on stage. The documentary primarily stitches together footage from his iconic Las Vegas residencies in 1970 and 1972, offering a dazzling display of over two dozen songs – including classics like “That’s All Right,” “Burning Love,” and “In the Ghetto” – with a rich soundtrack featuring even more of his repertoire.

The film transports viewers to a dream concert experience, exceeding anything fans could have witnessed in reality. Luhrmann and editor Jonathan Redmond assembled and painstakingly restored over 50 hours of once-lost footage from Elvis’s earlier concert films, “Elvis: That’s the Way It Is” and “Elvis on Tour,” strategically utilizing soundbites from archival interviews and live albums to allow Elvis to narrate his own story. The cooperation of multiple rights holders to bring this project to fruition is, as one observer noted, something of an entertainment industry miracle. It’s a project that likely wouldn’t have happened if Luhrmann’s 2022 biopic had flopped at the box office.

“EPiC” feels like a companion piece to the earlier film, borrowing its aesthetic style and narrative flow, including the same remixes and rearrangements of songs used in 2022, and even the same spangled, gaudy credits design. One key difference is the distributor: NEON is handling “EPiC,” while Warner Bros. Released “Elvis.”

The film quickly establishes the essential framework of Elvis’s comeback. When he retook the stage in 1969, it had been nine years since he’d performed before a live audience, and his appeal had waned. Reports from that comeback show indicated that most of his fans were over 30, with one 25-year-old attendee admitting he was there out of nostalgia. Luhrmann juxtaposes this return with images of car crashes and missile attacks, suggesting the cultural upheaval of the era.

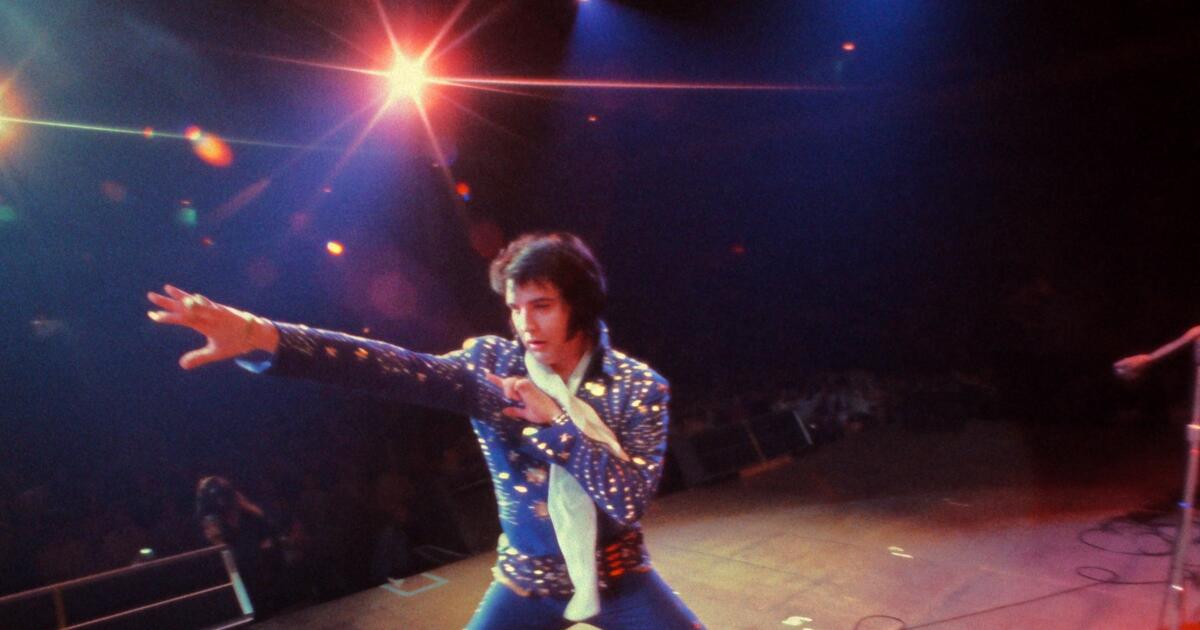

“EPiC” then picks up a year later, after Elvis proved he was still a smash. No longer constrained by moral panic, the Army draft, or the Hollywood industrial complex, this is the King at arguably the high point of his career, right before his 1973 divorce from Priscilla Presley, after which his mood and health began to decline. This Elvis comes across as confident, breezy, comfortable, and funny. In one scene, he jokes about the difficulty of lunging to the ground in a tight jumpsuit – an outfit he adopted because he was nervous about ripping his pants.

Later, he playfully alters the lyrics to “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” to croon, “Do you gaze at your forehead and wish you had hair?” The camera often lingers close to his face, capturing the sweat on his cheeks and lashes shimmering under the Vegas lights. His spell over the crowd feels both intimate and volcanic. The film excels at capturing his charisma, particularly when he focuses his energy on an unsuspecting backup singer during “Suspicious Minds,” hypnotizing her with the skill of a snake charmer before playfully lunging in her direction, eliciting a jump and a giggle.

While the film familiarizes viewers with the faces of his band members, it doesn’t bother to mention their names, even in the credits. This feels like an oversight, but the film is more concerned with how the concert *felt* than with how it came to fruition. It’s delightful to see that Elvis gives as much of himself in a small setting as he does on a massive stage, losing himself in the beat and gyrating his pelvis with machine-gun-like speed.

The film includes a montage of overwhelmed female fans, from a sobbing little girl clinging to his arm to a glamorous woman in a revealing minidress sneaking under the curtain. The ladies tug on his scarves and toss bras at him, one of which he playfully wears on his head. Surprisingly, Elvis reciprocates the affection, kissing fans who grab and kiss him, even after wading into a sea of admirers and emerging with the chains on his jumpsuit torn off.

In lieu of delving into Elvis’s off-stage reality, Luhrmann deepens a song’s emotional impact by cutting to personal photographs that are slightly out of context. As Elvis sings the line, “And I miss her,” from a ballad about a bad husband, the film shows a shot of his deceased mother, Gladys. “Always on My Mind” becomes a moving acknowledgment of Priscilla and their infant daughter, Lisa Marie. Otherwise, Luhrmann focuses solely on celebrating the positive aspects of Elvis’s life, presenting a vision of ecstasy without the agony.

Any hint of crankiness has been stripped away. While we hear him fielding nosy questions from the press, the closest Elvis comes to snark is when he sits on a stool to play “Little Sister.” He sings the chorus, then speeds up the tempo and briefly belts out The Beatles’ “Get Back” before smoothly transitioning back to his own song – a subtle jab at the British Invasion.

Luhrmann seems to have a score to settle. In the Butler version of “Elvis,” he argued that, as big an artist as Elvis was, he should have been even bigger. Colonel Parker, Elvis’s manager, kept him on a leash, tethering him to middling B-pictures and casinos. The Beatles invaded his country, yet he never played a single gig in theirs. The film suggests that if Elvis had traveled the world and explored different musical influences, he might have become an even greater artist.

With “EPiC,” Luhrmann wants to ensure we don’t miss that point. He even scores footage of Parker to “The Devil in Disguise,” suggesting that every religion needs a villain. The film, isn’t just a concert; it’s a meticulously crafted shrine, elevating Elvis Presley to something approaching a deity for a new generation.