The Early Universe Was a Surprisingly Soupy Liquid, LHC Data Confirms

In the moments immediately following the , the universe existed as a state of matter so extreme it defies everyday intuition: a trillion-degree plasma of fundamental particles. Now, researchers at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have provided the first direct evidence that this primordial “soup,” known as quark-gluon plasma (QGP), behaved not as a gas, but as a nearly frictionless liquid, sloshing and swirling with surprising fluidity.

This QGP, the hottest liquid ever to exist, existed for only a few millionths of a second before expanding and cooling into the protons and neutrons that eventually formed atoms. Understanding its properties offers a unique window into the conditions of the very early universe, a period inaccessible through direct observation.

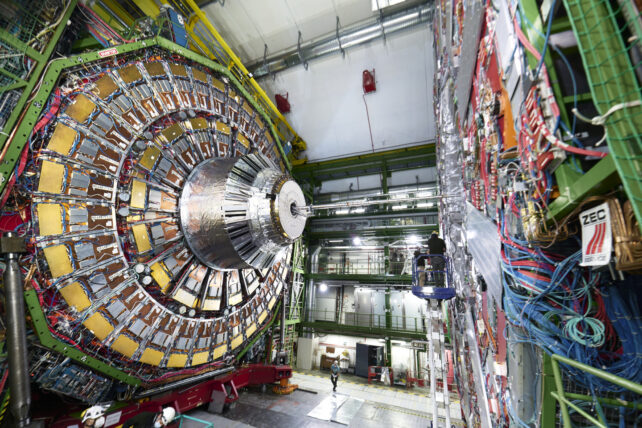

The research, conducted by a team from MIT and CERN, involved recreating conditions similar to those immediately after the Big Bang by colliding heavy ions – specifically, lead ions – at nearly the speed of light within the LHC. These collisions generate fleeting droplets of QGP, allowing scientists to probe its characteristics.

The key question driving the experiment was how particles move *through* this incredibly dense medium. Does a quark, one of the fundamental constituents of matter, interact with the QGP in a way that suggests a cohesive fluid, or does it scatter randomly as if moving through a gas? Previous experiments struggled to provide a clear answer due to the complexity of the collisions and the short lifespan of the QGP.

The MIT and CERN team employed a novel analytical strategy to overcome these challenges. They focused on tracing the motion of quarks through the QGP and mapping the energy distribution within the plasma following the collisions. This involved analyzing data from over 13 billion collisions, a massive undertaking requiring sophisticated data processing techniques.

“Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup,” says physicist Yen-Jie Lee of MIT. The observation of a “wake” effect – where the quark transfers energy to the plasma as it moves, creating disturbances analogous to the wake of a boat – provided compelling evidence of the QGP’s liquid-like behavior.

To isolate the quark’s influence, the researchers didn’t focus on the more common quark-antiquark pairs produced in LHC collisions. Instead, they searched for events where a quark was created alongside a Z boson, a neutral particle that doesn’t interact with the QGP. This allowed them to observe the wake created by the quark without interference from its counterpart.

The analysis revealed that the QGP responded to the passing quark in a manner consistent with a fluid, slowing the quark down and creating a discernible disturbance. This confirms theoretical models, such as one developed by MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, which predicted the fluid properties of QGP.

“By analogy, when you have a boat moving through a lake, the wake is water behind the boat that is moving in the direction of the boat. The boat has transferred momentum to some region of water, which is ‘following’ it,” explains Rajagopal. Detecting this wake within the QGP, however, was a significant technical hurdle, requiring the analysis of incredibly fleeting and complex interactions.

Rajagopal describes the findings as “definitive, unmistakable evidence” of the QGP’s liquid-like behavior. The new technique developed by the team provides a powerful framework for exploring similar phenomena in other high-energy collisions, potentially unlocking further insights into the fundamental nature of matter and the evolution of the universe.

“In many other areas of science, the way you learn about the properties of a material is to disturb it in some way, and measure how the disturbance spreads and dissipates,” Rajagopal added. The LHC, in this case, serves as the ultimate tool for “disturbing” the primordial soup and observing its response.

This research is published in the journal Physics Letters B.