The building tax has existed for more than 50 years. To avoid anarchy and plan for the future, this is applied even in unserviced neighborhoods within the urban perimeter, as explained by Denis Nshimirimana, secretary general of the CFCIB, engineer and former minister of Public Works and Equipment. from 1998 to 2001

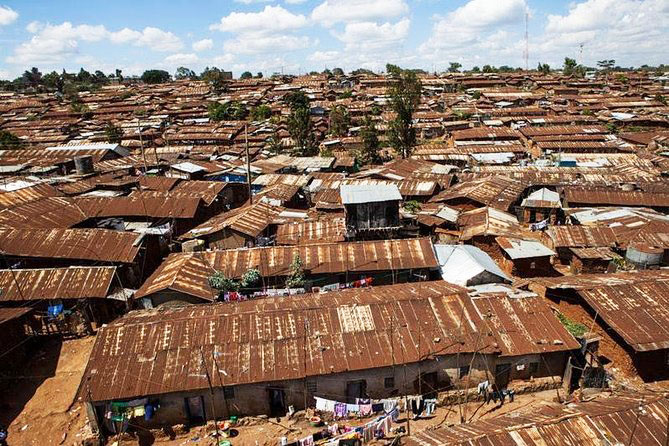

Spontaneous neighborhoods give rise to slums. To avoid this, building authorization must be required and, therefore, a building tax for any construction within the urban perimeter (Kibera slum in Nairobi).

“The principle of taxes is to tax the rich more than the poor. If a citizen is capable of building a house for 500 million FBu, 300 million FBu, it is someone who has income, who owns wealth. It is therefore normal that he pays a building tax. Moreover, it is possible that this building tax will be revised upwards in the coming years,” notes Denis Nshimirimana, secretary general of the Federal Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Burundi (CFCIB).

This after the Burundian Revenue Office (OBR) released a press release on December 13, 2023 recalling the payment of the building tax on construction in the urban perimeter in accordance with article 100 of law n°1/16 of June 28, 2023.

This tax stipulates that the construction of a house in the urban perimeter, on serviced and unserviced land, must first have a building permit subject to a building tax of 0.8% calculated on the estimate of a lower amount or equal to two hundred and fifty million Burundian francs (250 million FBu) and 2% on the estimate of an amount greater than 250 million FBu.

And to continue: “All owners of current construction sites or those who wish to begin construction within the urban perimeter are reminded to pay this tax without delay, failing which they are exposed to sanctions in accordance with the ‘article 100 of the budget law’.

A legal tax

Mr. Nshimirimana recalls that the building tax is legal. For him, ever since cities existed, building authorization has been required. This is because cities have master plans for development and town planning.

“In addition to these plans, there are specific development and subdivision plans. This means that in a city, you cannot build any way you want. In each subdivision, there is what we call the occupancy or town planning regulations,” he specifies before informing that it is in these town planning regulations that we impose, for example, We must build high, on the ground floor plus 2 levels, plus 3 levels or even more. This town planning regulation imposes all construction standards.

Mr. Nshimirimana points out that in Burundi as elsewhere, when you present a plan to the town planning department to acquire a building permit (building authorization), you have to pay a certain amount. For more than 50 years, the building tax has been set at 0.6%. The budgetary law in force sets it at 0.8% for constructions whose estimate is less than or equal to 250 million FBu and at 2% for constructions whose estimate is greater than 250 million FBu.

This supposes, he specifies, that in all urban centers of Burundi, no one is authorized to build a house, a fence, rehabilitate a house or modify the plans without prior authorization from the town planning services. Even if it is a simple fence, you must pay the building tax in relation to the estimate for the fence.

The former Minister of Public Works and Equipment insists that the building tax is not new. According to him, people seemed surprised, while those who built in Kinindo, in Kibenga, in Kigobe, in district 10, in district 9, in Nyabugete paid this tax.

Besides, he admits, the amount fixed is insignificant. “Let’s take for example a house whose estimate is estimated at 200 million FBu. The building tax he will pay will be approximately 1 million 500 thousand FBu. Which is normal,” says Mr. Nshimirimana.

Furthermore, he insists, there are quite a few taxes, sometimes higher than the building tax, like income taxes, salary taxes, taxes on results (at the end of a financial year it is 30% of the profit made).

It is in this spirit that the State could tax large incomes to ensure its missions, including the construction of roads, schools, hospitals, the payment of civil servants’ salaries, etc.

Hence it must detect the sectors which are either not taxed or under taxed.

Prohibit slums

Mr. Nshimirimana announces that imposing constructions erected in unserviced neighborhoods is a necessity. This is to avoid anarchy, the birth of spontaneous neighborhoods, that there are houses not served by roads and to ensure compliance with the water code.

According to him, before granting building authorization, we check whether the construction will be served by a road. If there is no path, this authorization is not granted. “Otherwise, we would witness the birth of spontaneous neighborhoods which create slums. Which is a safety hazard,” he laments.

The general secretary of the CFCIB informs, for example, that in Nairobi, Kenya, there is a slum called Kibera. It has a population estimated at 1 million inhabitants. “There, the police don’t even enter. It’s a bandit neighborhood where criminals and drug users hide,” he regrets.

However, Mr. Nshimirimana recognizes that there are slums all over the world. At the time, in Bujumbura town hall, the Mirango I, Mirango II and Gituro neighborhoods of the Kamenge zone in the Ntahangwa commune were spontaneous neighborhoods. We restructured them later by force. In the Buyenzi zone located in the Mukaza commune, the Kinogono district was a spontaneous district. It was razed by order of the presidency in 1985.

For this former authority of urban planning services, it is necessary to require building authorizations in unserviced neighborhoods to respect the 25 m along the rivers, a setback of 150 m along Lake Tanganyika, except for old constructions. This is to avoid landslides.

Mr. Nshimirimana indicates that raising awareness about this tax is not necessary since it is not a new phenomenon. However, he continues, perhaps the press release had to be co-signed by the commissioner general of the OBR and that of the Burundian Office of Urban Planning and Housing (OBUHA). It is the latter who issues the building authorization.

Urban perimeters are demarcated by known patterns. If we decide to extend the urban perimeter, the obligation of a building authorization is required even if the inhabitants are not expropriated as indicated by Mr. Nshimirimana. So, let OBUHA or the minister’s office make an official communication to carry the information further.